Of the passel of hastily written books now on the shelves discussing the financial crisis and what to do about it, The Wall Street Journal Guide to the End of Wall Street as We Know It by Dave Kansas may have the best title. But like the other members of its micro-genre, it is not likely to become an enduring classic. Kansas is a web and newspaper reporter by trade and the entire book can be usefully thought of as an extended magazine article, what in an earlier age might have been called a pamphlet. It was written over a few weeks in the last months of 2008, was on shelves as a paperback by the end of January, and will probably outlive its usefulness by late summer. It will next be seen many years from now when unearthed by a graduate student doing research into the contemporaneous reaction to the Panic of ’08, or whatever it is that the current crisis winds up being called.

But as a long magazine article, the book has its merits. If you weren’t paying close attention to events in the financial world last year and now feel at a disadvantage at dinner parties, The End of Wall Street will help. Even relatively close readers of news accounts will find tidbits and pieces of the big puzzle they have missed. For example, the book points out that the average FICO scores of sub-prime borrowers actually improved as the housing bubble grew. While the sub-prime borrower of ten or fifteen years ago might have been sub-prime due to a bad credit history, by 2006 a sub-prime borrower typically had adequate credit but was buying more house than he could truly afford.

Kansas also provides a modicum of analysis and reflection, roughly what you would expect from a reporter given a book to fill but only a short time to do it. He deftly points out that the troika at the helm of the government’s handling of the crisis in the fall of 2008 was made of Fed Chairman Ben Bernacke, New York Fed President Tim Geithner and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Kansas does not say it, but he clearly means the reader to notice that the new administration has merely contracted that troika into a duo.

And although he cannot resist blaming the Usual Suspects of crooks and overly clever bankers, Kansas does so with a light hand. The fiasco in mortgage bonds was propelled by the same forces that propel the economy in good times, avarice and optimism. As Kansas deadpans, “Creating new regulations that will eliminate greed is practically impossible.” Nor, he might have added, is it necessarily a good idea.

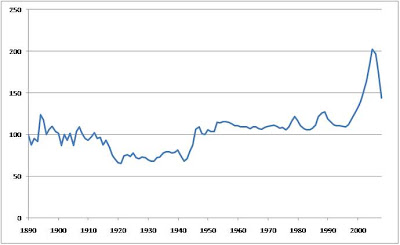

The fuse for the powder keg was lit in June 2006 when, according to the S&P Case-Shiller Indexes, house prices in the US peaked, having gone up 190% in ten years. It took some time to play out, but after years of aggressive lending and borrowing on the almost universally held theory that house prices never go down, the result was nearly pre-ordained. There are wrinkles that made it worse, such as the peculiar structure of the mortgage bond market, but as Kansas makes clear, these are complications to the core disease. A truly vast number of bad loans got written and, due to the nature of the beast, they all went south at the same time.

It is what happened next that made our current situation dire. As Kansas tells us, within living memory there have been several large-scale financial crises that failed to destroy Wall Street, and some of those failed even to cause a recession. The tech-telecom bubble burst at the start of this decade, vaporizing trillions in stock market wealth and littering Wall Street with worthless telecom debt. That came only a few years after the Asian Crisis and Russian Default Crisis culminated in the collapse of Long Term Capital Management, which caused dramatic late night meetings of the leaders of Wall Street, but not, apparently, any long term repercussions. And a few years before that, almost the entire S&L industry went up in flames.

Kansas calls these disasters Dog That Didn’t Bark moments, events that historians will realize hold significance for what did not happen rather than what did. Indeed, the fact that no really terrible damage was done only encouraged further risk taking. But in retrospect, the financial system was lucky to weather those storms as well as it did. The seawalls were just strong enough and the ad hoc and somewhat haphazard government rescue efforts were just adequate enough to see us through. When a slightly bigger hurricane made landfall it was revealed just how insufficient the financial system’s defenses had really been all along.

The levees were breached on Monday, September 15, 2008. That was the day Lehman Brothers failed, defaulting on its debt and turning what had been an atmosphere of fear and foreboding into one of panic. Investors reasoned that if the debt of a firm as significant as Lehman could become worthless then nothing was safe. All of a sudden everybody started hoarding cash, refusing to lend to anybody under any circumstances.

Lehman had been widely known to have been in serious trouble for some time, so a person might wonder why its failure could have come as such a shock to the system. As late as the Friday before, the credit default market was pricing the likelihood of a Lehman default in the following year at only 7%. This apparent incongruity can be explained by the fact that almost everybody on Wall Street believed that even though Lehman was probably insolvent, the government would never allow such a key player to default. Of course, that is exactly what happened.

[Stay tuned for part 2 of this review early next week.]