Until just a little while ago a fear of deflation was all the rage. In-the-know types nodded their heads gravely and showed erudition by expressing a fear of something that hasn’t been a problem in this country for 75 years. And they were right to fear it. Deflation is a really nasty thing. More than anything else, it is what made the Great Depression great. But as it happens, our guy at the monetary controls, Ben Bernanke, is a particular expert on deflation and the Great Depression. He may or may not succeed in steering our economic ship clear of the shoals, but deflation is one particular rock he is sure  not to hit.

not to hit.

Prices did decline in the fourth quarter of 2008, down –3.3% as measured by the Consumer Price Index. Annualized out, that’s a very scary –12.4%. But, knock on wood, that was a brief episode that is now over. The Fed has been working furiously to pump as much money into the economy as possible, doing everything short of handing out bags of the stuff on street corners. Prices were up in both January and February, totaling +0.7%, which is a +4.3% annual rate.

So the Informed Consensus Fear has shifted from being focused on deflation to an uncertain fear of both deflation and inflation. Personally, I predict inflation. Maybe not in 2009, but in 2010 and beyond.

Read more »

Moolanomy has a regular feature called “Ask The Expert With Larry Swedroe” in which readers ask a question related to investing. Last week the question came from the host of Gather Little by Little, who insists on calling himself Glblguy. Apparently in earnest, he asked “When deciding to purchase  individual stocks, what process do you go through to determine if the stock is a good buy or not?”

individual stocks, what process do you go through to determine if the stock is a good buy or not?”

Swedroe was firm and to the point in his reply. “No one should own individual stocks.”

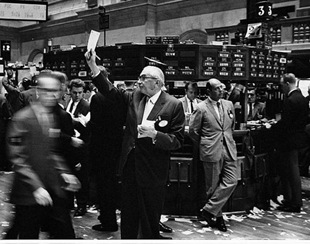

As painful as it is for me to write this, I basically agree. Painful not just because agreeing with others is against my nature, but because I love buying individual stocks. Few things are as much fun. The stock market is an ever-changing universe of stories, ideas, and theories of the future where I can match wits with other participants and actually bet money on the proposition that I am smarter than everybody else. Awesome.

But I am a professional. I trade stocks for a living. (Or at least I used to, before, uh, certain unfortunate developments.) You, I am assuming, are a productive member of society with a job producing a thing or service of value.

Read more »

It seems that when journalists can’t think of anything else to say about the latest slaughter on Wall Street they point out that the stock market is now back to where it was X years ago. It’s not a meaningless comparison.

On Friday the S&P 500 closed at 683.38, up 0.12% over the close the day  before. Prior to Thursday, the last time the S&P closed at that level was September 20, 1996. Old guys like me think that was just yesterday, but it was actually rather a while ago. Clinton (the husband) was running for reelection. The internet stock craze was just beginning. Steve Jobs hadn’t returned to Apple yet and Amazon and eBay were both still privately held.

before. Prior to Thursday, the last time the S&P closed at that level was September 20, 1996. Old guys like me think that was just yesterday, but it was actually rather a while ago. Clinton (the husband) was running for reelection. The internet stock craze was just beginning. Steve Jobs hadn’t returned to Apple yet and Amazon and eBay were both still privately held.

Does it make sense that the 500 largest companies in America are now worth what they were 12 1/2 years ago?

Of course, simple price level is not the only way to judge what stocks cost. Consider price earnings ratio (PE), what you pay per dollar of corporate profits. What the S&P 500 companies will probably earn in 2009 turns out to be roughly comparable to what they earned in 1996. But that’s not apples to apples, because in 1996 the economy was humming along in a boom and today the economy is in recession. (We hope.) To normalize the cyclicality out and get a handle on the gross earnings power of the S&P 500, Yale’s Robert Shiller has popularized PE10, which is the ratio of price to the average earnings over the previous ten years. Plug in Friday’s close to his spreadsheet and you get a value of 11.8. The last time we saw 11.8 was in January 1986.

Read more »

In 2010. Or not.

I recently wrote a post on how to choose between the two kinds of IRA, traditional and Roth. In a nutshell, the big deciding factor is the tax rate you are paying now versus what you will pay when retired. If you are paying a higher rate now, go traditional. If you will pay a higher rate when retired, then Roth is for you.

The core difference between the IRA types is deceptively simple. With a traditional, you don’t pay taxes on money you put in, but do pay taxes on the way out. A Roth is the other way around, the money that goes in is after-tax, but the money that comes out is tax free. But like that old bit about the butterfly’s wings causing a storm, this clear difference between IRA types propagates into uncountable obscure details.bouncy castle sales

One of those dark corners of the IRA world is the option to convert an existing traditional IRA into a Roth, which involves paying income taxes on the amount converted. (And no, there is no such thing as a conversion in the other direction that would cause a big tax refund.)

Currently, and until next year, you cannot convert if you have an income over $100K. Not only does that rule go away next January, but there is a special 2010-only deal: you can delay the taxes due and spread them out over two years, 2011 and 2012, which is an interest-free loan from Uncle Sam. (In any other year, it would be all due in the year in which you convert.)

Is this a good idea for you? Two things need to be true. First and foremost, you need to be pretty sure that your income tax rate in 2011 and 2012 will be lower than the tax rate you pay in retirement. This is the usual traditional vs. Roth question, made a little harder because you need to guess your tax rate in a few years from now as well as your tax rate in retirement.

Read more »

Yesterday Wall Street Journal columnist Brett Arends reported that from 1995 you would have been better off in a money market fund than the stock market. Apparently the meaning of the Dow hitting a twelve year low took a while to sink in. Arends also tells us that “Thanks to inflation, investors have lost ground simply if they haven’t gained it.”

Today Jason Zweig picks up the theme with a column entitled “After the Crash, Stocks May Face Long Road Back; History Suggests There’s No Guarantee of Quick Rebound; Buy and Hold — for Decades?” Zweig reveals the not at all shocking truth that just because the stock market went down a lot in the last year or two that does not mean it will necessarily go back up a lot in the next year or two.

He cites a soon to be released report from a professor of finance saying that the expected time that it will take the Dow to regain its 2007 high is nine years. That is, it has an equal likelihood of getting back to its peak after 2018 as before. Zweig says that this “shocked” him. Really? In round numbers the stock market is down 50% from the peak, so getting back up requires a gain of 100%. If you are a little pessimistic and assume an 8% average return from stocks, that will take 9 years. If you think 10% sounds right, then it will take about 7 1/2 years.

There is a powerful psychology of denial that affects many people, personal finance columnists at national newspapers included. The numbers on the 401(k) statement in early 2007 just seemed so real and substantial that it is hard to acknowledge that today’s much lower numbers are just as real. People tend to expect a V pattern in stock prices, that a few really bad years are inevitably followed by a few really good years.

The stock market doesn’t work that way. It can’t. It’s like a law of nature. The market cannot let itself be so easily predicted. Knowing what happened one year tells you (almost) nothing about what will happen the next. Since 1871 the stock market (as measured by the S&P 500) has had 38 down years. Excluding this year, the average return the year after losing money is +11.63%. The S&P has also gained more than 20% in a year 38 times. The average return in years following big gains is +12.27%.

There is obvious incredulity in the question “buy and hold — for decades?” But the straightforward answer is “Yes, of course.” Did you think that you could guarantee fat stock market returns if you were willing to stick it out for five or ten years? You can’t, and that’s something that all stock market investors, and all Wall Street Journal columnists, need to know.

not to hit.

not to hit.