I have only respect and contempt for Suze Orman.

On the positive side, it would be hard not to admire Orman’s talent and achievements. She is undoubtedly the most effective and popular personal finance guru in America today. Suze Orman’s 2009 Action Plan is her seventh consecutive New York Times bestseller. She has won two Emmys. Last year Time named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world. To put that last achievement in perspective, consider that the Pope did not make the cut.

Alas, this highly tuned and powerful machine is used to bring her vast audience fairly mediocre and amateurish advice. At best, what Orman tells her readers and viewers is pedestrian and obvious. At other times it is dangerously specific, assuming unstated facts about the reader’s situation. And once in a while it is just plain wrong. But wasting her abilities with weak content is not the chief reason I have contempt for her. She also has a righteous new-age shtick about courage and honesty which is not only grating, it is hypocritical.

Suze Orman’s 2009 Action Plan is her reaction to the current economic crisis. (Of course, given its success, I would expect an Action Plan to appear annually every January from now on, crisis or no.) It is one of many quickie books on similar themes that have appeared in the last few months. Orman’s was finished on November 19, 2008 and on bookshelves as a paperback by mid-January 2009. As would be expected, it is not very long and lacks much in the way of a coherent organization. The great majority of the book is in the form of an extended FAQ, with “situations” that could have easily been phrased as readers’ questions followed by short answers or “actions.”

The slim volume does contain a few longish bits of advice and explanation. One of these is the second chapter of the book, entitled “A Brief History of How We Got Here.” It is not merely brief (11 pages) but shallow as well, what you might expect from a bright high school student asked to summarize the economic situation based on accounts taken from one of our nation’s lesser tabloids. Admittedly, Wall Street and the economy are not Suze Orman’s fields of expertise, but this section betrays a remarkable lack of knowledge about how indeed we got here.

For example, Orman explains that in reaction to the low interest rates of the middle of this decade, the “too-smart-for-their-own-good minds of the financial sector” “bundled the prime and sub-prime mortgages into one investment, called a Credit Default Obligation (CDO).” Actually, CDO stands for Collateralized Debt Obligation, prime and sub-prime mortgages are generally segregated (not that that helped) and CDOs became the standard method for structuring mortgage bonds twenty five years ago. How CDOs were invented is described entertainingly in Michael Lewis’ bestseller Liar’s Poker (1989) which until recently I had thought everybody involved in finance and over the age of 40 had read.

The Orman view on what went wrong in the global economy begins and ends with American house prices and mortgages. That is like blaming a warehouse fire on faulty wiring without mentioning that the building was full of fireworks and that the sprinkler system failed. But no matter. 2009 Action Plan is for consumers, so limiting the explanation of what went wrong to consumer-oriented factors is not the worst thing imaginable. Orman ends the chapter by summing up that “the mortgage crisis is the most vivid example of how dishonesty and greed leads to financial destruction” and exhorts her readers to become honest with themselves about their own finances.

That’s a sentiment with which it is certainly hard to disagree. Truth and candor is a recurring theme of Suze Orman’s, both in this book and elsewhere. It would be much more convincing if Orman was herself more honest about how her advice about houses has changed over the past few years.

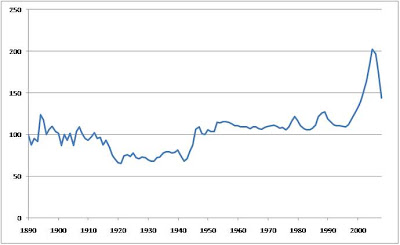

2009 Action Plan tepidly endorses buying a house, saying that “over time a home can be one of the most satisfying investments you can make” (p. 147) and clarifies that your house “will, on average, rise in value at a pace that is only one percentage point above inflation.” (p. 154.) I have no objection to either of those points, but isn’t this the same Suze Orman who called home buying “one of the best known investments” (The Laws of Money, 2003 & 2004, p.131) just a few years ago? In 2009 Action Plan Orman is repeatedly strident about not taking out a loan from your 401(k) or tapping your IRA for any reason short of dire emergency, and yet in The Courage to Be Rich (1999 & 2002) she suggests doing both to raise money for a house down payment (p. 223.) In 2009 Action Plan Orman condemns adjustable rate mortgages and says that a 30 year fixed is a “requirement” for home buyers (p. 148.) In The Courage to Be Rich she discusses both flavors of mortgage favorably and lists reasons you might be better off with an ARM. (p. 254.)

There is no shame in having been much more enthusiastic about houses a few years ago. As far as I can tell, all personal finance writers urged their readers to buy houses in the Good Old Days, and Suze Orman was actually more cautionary than most. And circumstances have indeed changed in the meantime. But for a person who lectures continually about the importance of honesty and speaking the truth about money, would it be too much to expect a modest mea culpa? Wouldn’t her criticism of the “dishonesty” of those who borrowed too much to buy more house than they could afford be more persuasive if she conceded that the chorus of personal finance advisers, Suze Orman included, egged them on?

[Click to the second half of this review here.]